Dr

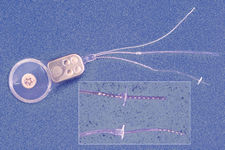

Bruce Gantz's Iowa/Nucleus Hybrid Cochlear Implant

|

Treating severe hearing loss

has always forced doctors to make tough decisions. Cochlear

implants have long been used as a last resort when hearing

aids no longer cut it. Trouble is they tend to accentuate

high pitch sounds and destroy any residual low frequency

hearing. Ten years ago Dr Bruce Gantz, who heads the otolaryngology

department at the University of Iowa, decided the status

quo just wasn't good enough for his patients and set out

to come up with an alternative.

The result, his experimental hybrid

cochlear implant, melds bionic technology with traditional

hearing aids. But the key to his device is that it's

far less invasive than traditional cochlear implants

and appears to preserve low frequency hearing. "I started

with the concept of trying to stimulate only the areas

of the inner ear that seem to be major sources of hearing

loss — the high frequency areas. This fits most

people who have hearing loss due to aging, genetic causes

or noise exposure," he explains. The 2000Hz and higher

region is where consonants are interpreted. "When you

start losing significant hearing, speech becomes muddled

because you don't understand all the consonants that

are there," he says.

So far, 65 patients have been fitted

with Dr Gantz's hybrid cochlear device. And trials are

going well. "We've been able to save most of the low

frequency hearing in all those patients," he said. "People

who have an average of 25% word understanding with hearing

aids are up to over 70% word understanding with the

hearing aid plus the implant."

COCHLEAR

CONUNDRUM

Though originally only used in very extreme cases, more

recently cochlear implants have seen their indication

expand to folks with a modicum of hearing left. This

didn't sit too well with Dr Gantz. "There's a potential

downside of putting a traditional cochlear implant in

a patient who has some residual hearing because you'll

most likely destroy it."

Dr Gantz figured that smaller is

better. "We used a small electrode — only 0.2mm

by 0.4mm — whereas standard electrodes are about

1.2mm in diameter," he explains. When you start advancing

a traditional electrode into the cochlea, which is coiled

like a snail, it tends to ride against the outer wall,

pushing the device up towards the hair cells —

acoustic sensors that convert vibration into an electrical

signal in the inner ear. So by placing larger electrodes

in the cochlea there's a good chance you'll end up damaging

the inner ear. "Our thought was to try and limit the

amount of damage to only that area in the inner ear

where high frequency is," says Dr Gantz.

IN

ONE EAR

The Iowa/Nucleus Hybrid Cochlear Implant System —

as it's officially called — won't be widely available

for a while yet. "We're probably going to go to the

FDA mid-year or so and let them evaluate our results,"

says Dr Gantz. "Even then it will only be able to be

fitted by very specialized ear doctors because there's

still a risk to the inner ear and it will require some

training," he adds.

If they do come on the market,

what kind of patients would be right for the hybrid

device? "It'd be people who have a lot of trouble understanding,

who aren't able to use hearing aids very well to improve

their word understanding, and people with trouble hearing

in noise," says Dr Gantz.

And the device holds promise for

music-lovers too. "We're doing a lot of testing involving

music," says Dr Gantz. "Melody recognition in subjects

with the device is almost on par with those with normal

hearing because those low frequencies are preserved,

so it's a very important step. Most patients with [traditional]

cochlear implants don't do very well with music," he

adds.

|