Ever

felt like blowing up a hospital? You're not alone. When

Calgary General Hospital, built in 1953, was demolished

in 1998, the gathered crowd exploded with applause. Today's

hospital designers insist they're taking a more humanist

approach, but are the US-inspired mega-hospitals cropping

up across Canada really such a great idea for us? Ever

felt like blowing up a hospital? You're not alone. When

Calgary General Hospital, built in 1953, was demolished

in 1998, the gathered crowd exploded with applause. Today's

hospital designers insist they're taking a more humanist

approach, but are the US-inspired mega-hospitals cropping

up across Canada really such a great idea for us?

NOURISHING

BUILDINGS

McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) is about to test

those waters with its gargantuan mega-hospital in construction

west of downtown Montreal (another mega-hospital is

being planned northeast of downtown). "We're shifting

from an old paradigm where we fix the patients, to a

new paradigm where we nourish the patient and help them

heal themselves," enthuses Chief Planning Officer Mr

Jean Dufresne. "If you look at a brick wall all day,

patients don't heal as fast as when they look at a tree.

If you can reduce stress, the patients will heal faster

and their stay at the hospital will be shorter."

Not everyone's quite as sold on

the idea, though. "We don't know how patients or providers

are affected by these spaces," cautions Dr Patricia

McKeever, co-director of the Canadian Institutes of

Health Research Strategic Training Program in Health

Care, Technology and Place at the University of Toronto.

"No one has done evidence-based research to show that

new buildings are better than the old."

HEALING

ENVIRONMENT

Most early hospitals were utilitarian buildings stripped

bare with everything painted a sterile white. More recent

hospital designs have striven to create a "healing environment,

with a return to colour, human affect and a more intimate

scale," according to Dr Annmarie Adams, an associate

professor at the McGill School of Architecture. As director

of Medicine by Design, a project funded by the CIHR,

Dr Adams' top focus is the history of hospital architecture

in Canada.

The shift toward patient-centred

hospitals goes back to the late 70s when Canadian designers

rebelled against the boxy hospitals of the 50s. Then

came the financial squeeze of the 80s. "In the 80s there

were incredible changes in the way healthcare was delivered,"

says Dr McKeever. "IVs and ventilators went into patients'

homes — under fiscal pressure." The result was

that homes became more like hospitals, and hospitals

became more like homes.

CONTROL

FREAKS...

'Patients' rights' are the bywords of the 21st-century

planning movement. Ward-based hospitals were great for

nurses and doctors, but patients were left with nowhere

to hide from prying eyes during their hospital stay.

In Mr Dufresne's view, giving patients control over

their environment is key. "So we have a high ratio of

private rooms, which allow the patient to close their

door," he says. "There are places in the States where

children get to choose their own wall hangings. So we'll

offer kids a choice of posters, because some like Britney

Spears, some like Metallica."

Britney aside, Dr Adams isn't so

sure this is the way to go. "I'm worried about the trend

toward exclusively private rooms," says Dr Adams. "We're

blindly following US models, but we have very different

healthcare systems." It's still unclear if patients

will be charged for the privilege of their newfound

privacy.

...

AND MALL RATS

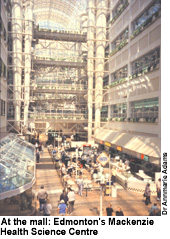

And the trend in the ultra-capitalist USA is to model

hospitals on Americans' favourite hangout: the mall.

Canada's hit the shops with gusto; Toronto and Edmonton

both already have successful mall-style hospitals. Toronto's

Hospital for Sick Children Atrium Patient Tower, built

in 1993, drew on the innovative design of the Walter

Mackenzie Health Sciences Centre in Edmonton, 1986 (pictured).

"Rather than looking like an office building, it looks

more like a mall," says Dr Adams. "It has a grand atrium

with a glass roof and many levels. Each area looks out

onto the others, so everyone can see everyone else:

you can see patients in wheelchairs and stretchers going

down to the food fair, sitting in lounges, watching

TV."

The mall look is no coincidence:

both hospitals were designed by Zeidler Roberts Partnership

Architects, the firm that gave us Toronto's Eaton Centre.

They're similar in more ways than one — the mall

hospitals literally have shops and a food fair. "We're

seeing the invasion of fast-food and retail outlets,"

observed Dr Adams. "You can get out of your room and

have a cheeseburger, buy a Roots t-shirt."

So will the MUHC look like a medical

mall? "Yes, absolutely!" says Mr Dufresne. "You want

to reproduce the environment people are comfortable

with."

The mall model may get people spending,

but there's no proof that it speeds up healing. The

new hospitals may be more comfortable, but Dr Adams

can't help noting the irony of the situation. "We spend

less time in them — patients are in and out in

a day."

|